|

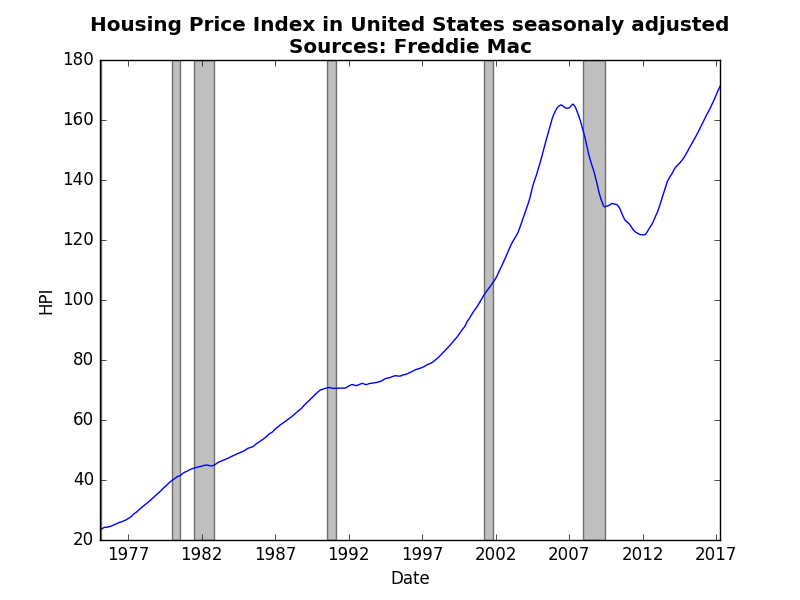

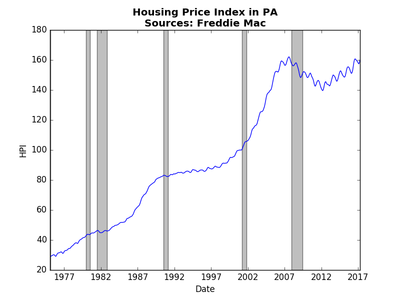

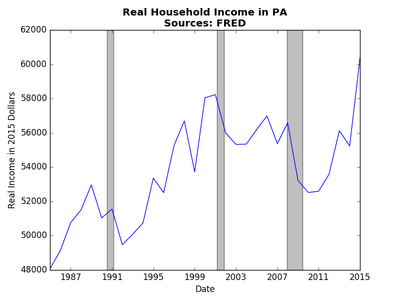

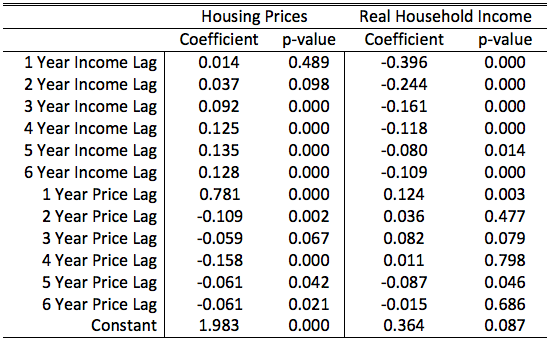

Housing prices in the US have crossed their pre-recession levels as shown in the graph below. Housing prices, much like many economic variables, tend to have an upward trend, usually exhibiting compound growth. This post uses state-level data on real household income and housing prices to explore the concept of endogeneity, or the chicken and the egg problem. In economics, we frequently need to disentangle a vicious (virtuous) cycle. An example of a vicious cycle, a poor people tend to be the ones who purchase lottery tickets, which comes first: being poor or buying lottery tickets. This type of story exists in house prices and income in Pennsylvania depicted in the graphs below. Though real household income displays more volatility (the HPI is monthly and not seasonly adjusted) the general trends are more or less the same. What we might want to know is whether housing prices impact real incomes or the other way around. Clearly as people earn more income they can afford to purchase a house. However, as we saw during in the lead up to the great recession as housing prices start to soar, more individuals receive income from real-estate, either through sales, rentals, or "flipping." Macroeconomists utilize the irreversibility of time as a way to control or mitigate endogeneity. Something that happens today surely cannot impact what happened yesterday. After converting the state-level data into annual growth rates we can evaluate how lags (old values) of data impact current values. The table below reports those results. In these tables we see an interesting pattern. First, and not surprisingly, the lag of the dependent variables are all significant. Past performance influences future performance. Real household income exhibits a significant but weak negative response to the past. If last year was a good year this year is likely to be a little worse. In contrast, housing prices exhibit positive response to the past. If last years housing prices grew by the same amount as the previous four you can count on a year that is at least as good if not better.

The more important results are the off-lags, or how past prices influence income and vice versa. For housing prices, we see a relationship that is not too surprising. A build up of positive real income over distant past will lead to an increase in house prices. Intuitively, several years in a row of positive income growth leads to higher demand for houses, which drives up prices. The impact of housing prices on income is less clear. A rise in last years prices increases income (and maybe even the 3 year lag as well), which makes sense, since as price start to increase we can expect more sellers to join in. However, the 5 year lag is puzzling. I suspect that this is an artifact of the great recession. What we found was that both stories have some truth to them. It seems that the strength and duration of the impact of income on prices seems more and longer than that of prices on income. Therefore, it seems more likely that the recent increases in housing prices are in response to increased real incomes rather than housing prices predicting future real income increases. Technical notes: both regression included fixed effects by state. Data was from 1986 to 2015 for all fifty states and DC.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed